WK4DS Amateur Radio Blog

Building a 60m Band Module for Ten-Tec Scout 555: Crystal Selection & Filter Design [Part 2]

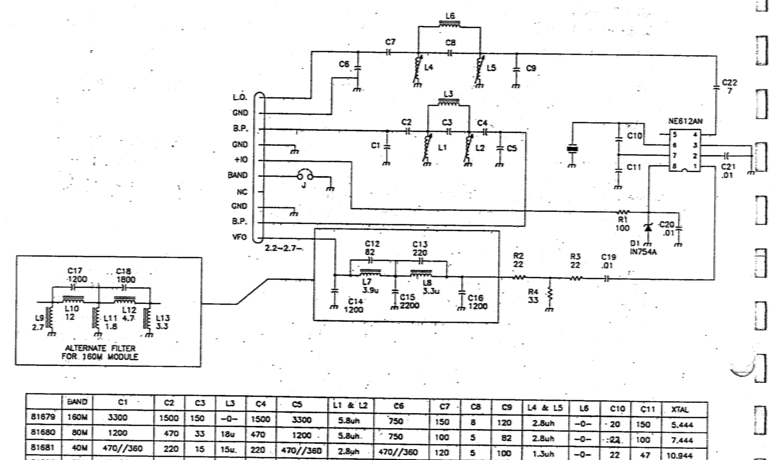

I figured the the mixer’s bandpass filter would be the same as the IF filter but turn’s out I was wrong here. I looked at the existing part values on the chart for 40 meters and 80 meters (remember that part about not having a formal education in this stuff?) and simply decided that the inductors were again too big and I needed them to have a slightly lower value instead.

Well, if this is the first post of my blog you have found about the 60 meter band module, please Read Part 1 for the complete background on this project. or a lot of stuff is not going to make sense…haha.

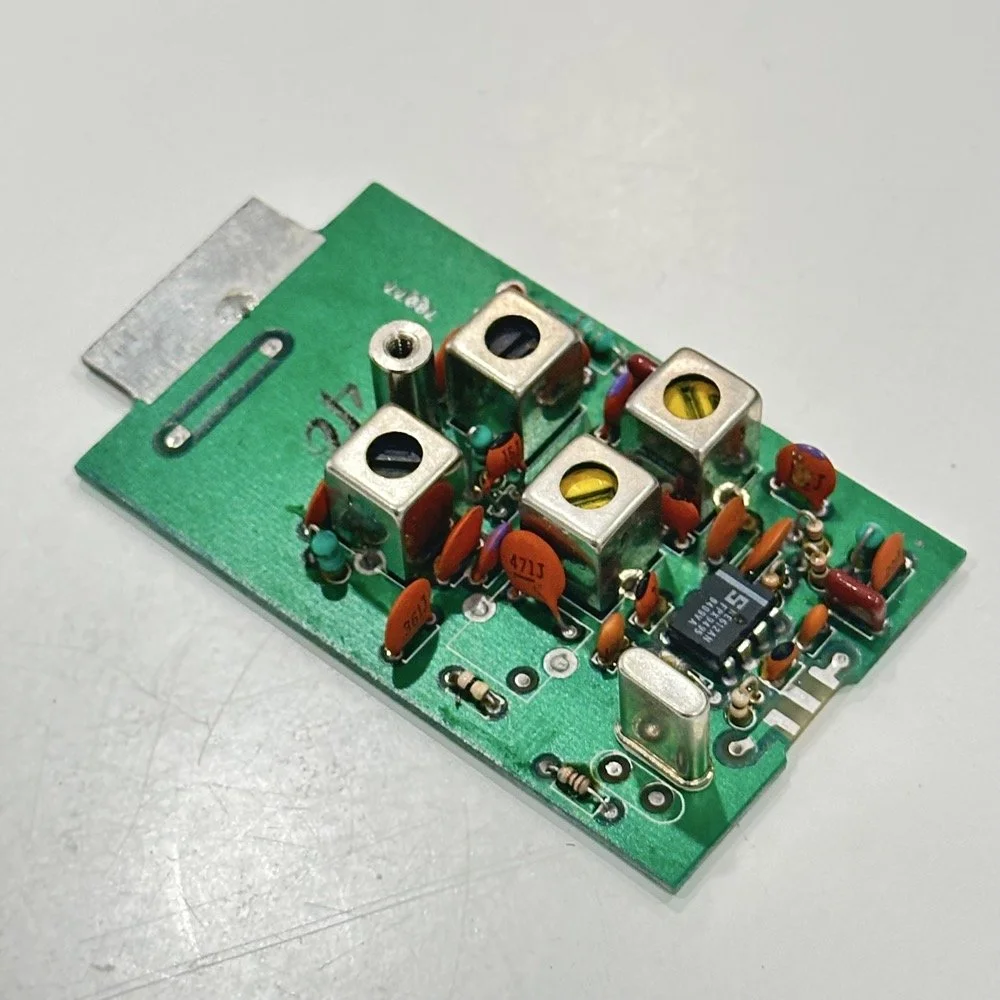

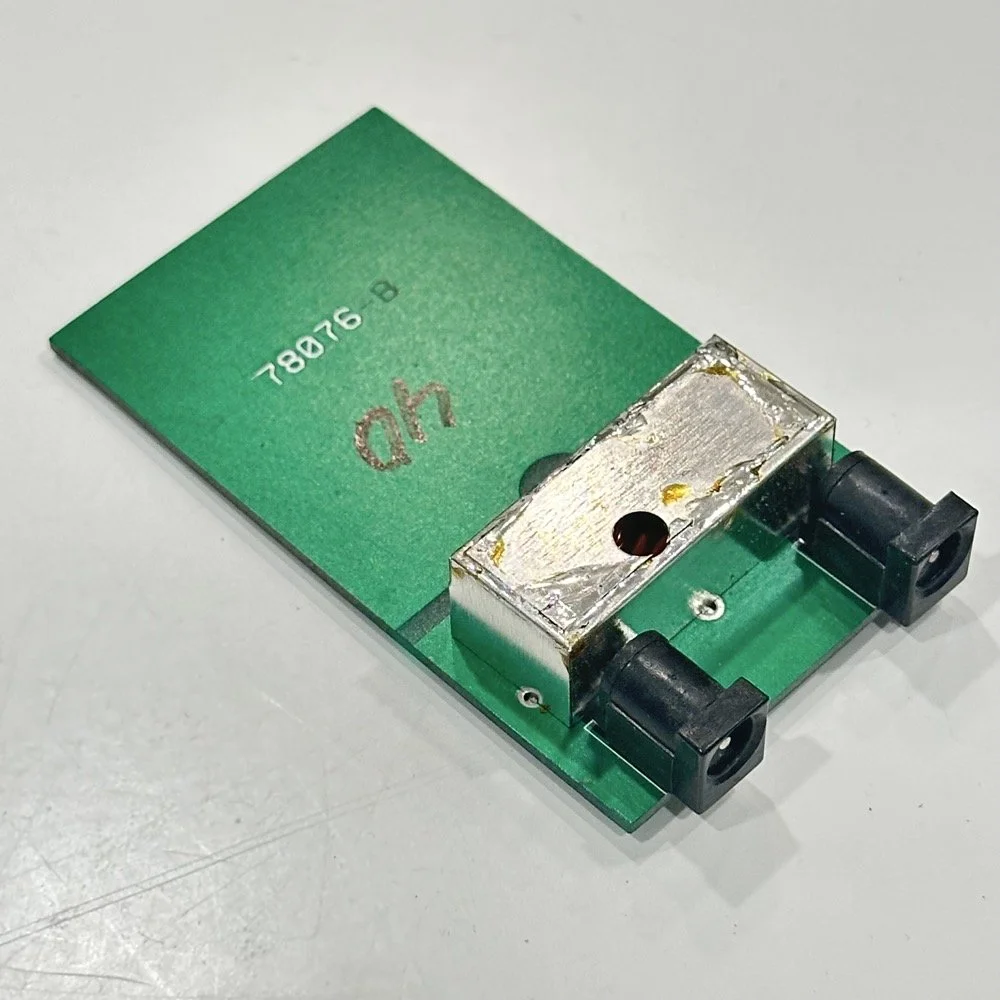

The donor about to undergo surgery to become a 60 meter band module.

As you know from last week, I was able to get all the filters updated except the output bandpass filter for the mixer and changing the crystal, so let’s get into that today.

I figured the the mixer’s bandpass filter would be the same as the IF filter but turn’s out I was wrong here. I looked at the existing part values on the chart for 40 meters and 80 meters (remember that part about not having a formal education in this stuff?) and simply decided that the inductors were again too big and I needed them to have a slightly lower value instead. This is where things get engineery..is that actually a word? It should be. I started by simply using an online calculator to figure the values for this filter based on the chart from NA5N’s Website and my own simple math of a mixed product of 11.442 mhz. It falls right in the middle of the 80 and 40 meter LO frequencies on his chart. So now I needed a crystal…

Luckily I didn’t need matched sets like when making a crystal ladder filter so I was able to find 9.218 mhz crystals on Digikey for reasonable money. The calculated crystal frequency I came up with was 9.242 mhz to land at 5.300 mhz. This radio will absolutely transmit out of band and it is the responsibility of the user to stay in legal band space so I figured this would cover the entirity of the 60 meter band. The NA5N chart shows the PTO minimum frequency is 2.2 mhz so that is where I started my math.

2.200 mhz (PTO min.)+9.218 mhz (PTO XTAL)=11.418 mhz (LO) - 6.142 mhz (IF) = 5.276 mhz

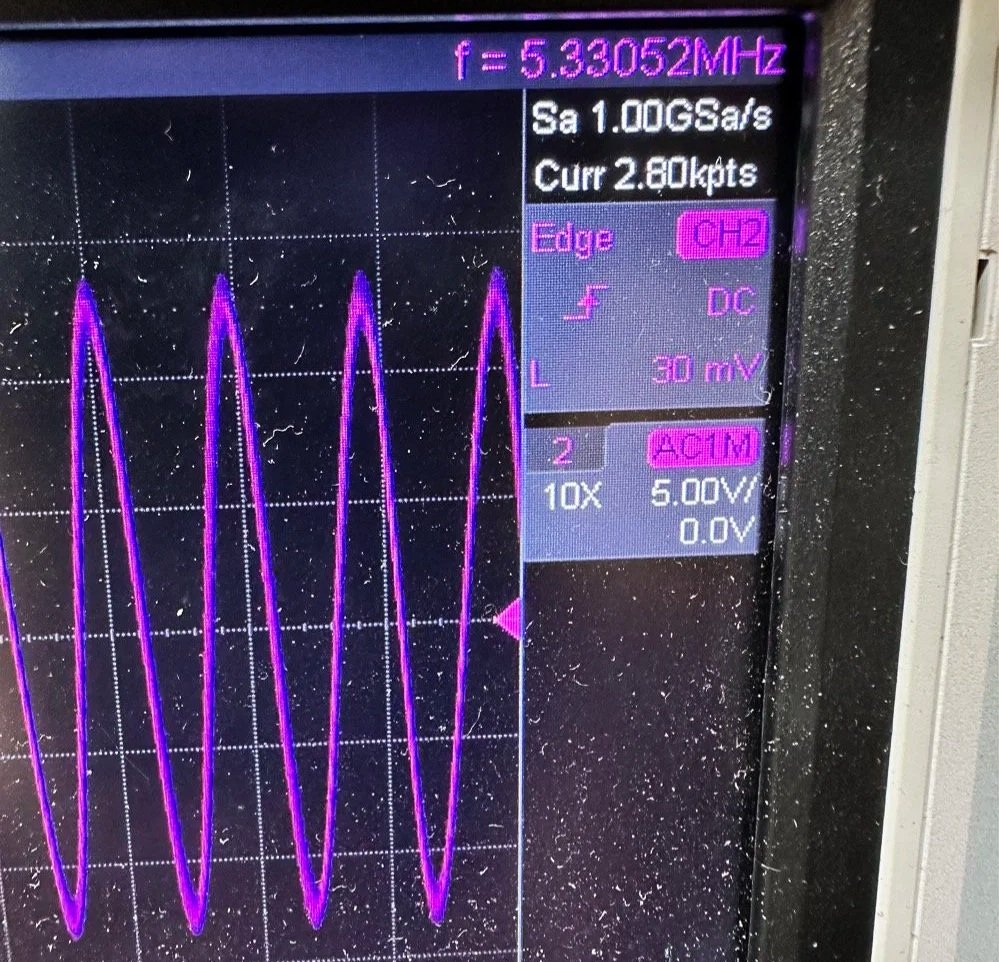

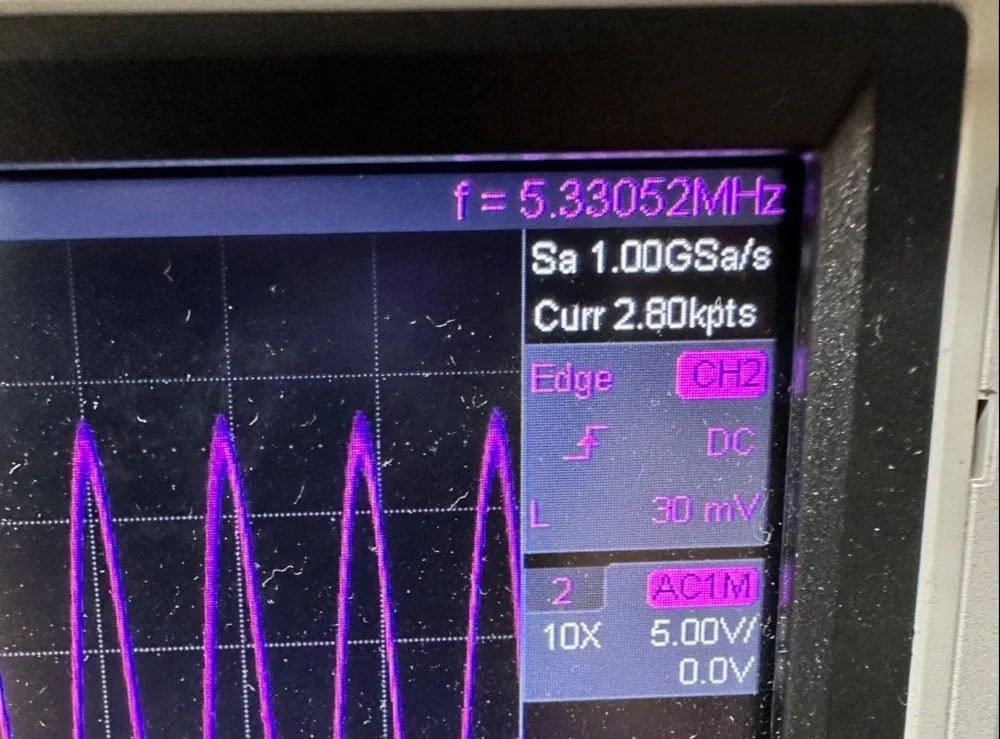

The entirety of the 60 meter band is from 5.3305 mhz to 5.405 mhz so this will work perfectly fine.

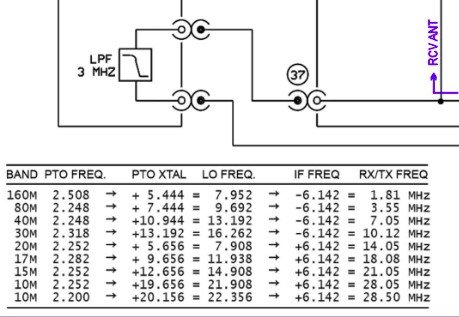

All this math starts to make sense when you look at the chart at the bottom of this page. That is why I keep linking it…haha. So I build out the band pass filter and install the new crystal when it comes in and … nothing… Well, it did something actually. It would not lock onto the frequency at all, it would attempt occasionally, but most of the time it would just scroll numbers on the display of the radio. It obviously was not working. I was sure I had built the filter right… (turns out I was dead wrong…again…I am starting to see a pattern here…haha).

As I would soon find out, I built the filter for the 40 meter IF by accident. At this point I had a lot of numbers floating around in my head and scribbled on various pages laying around the bench and one was where I had done some of the math around the 40 meter circuit for some reason and I inadvertently used those numbers to make the inductors with. Couple this with a trip out of town for a week and you will see where I lost my train of thought. Once I returned from the trip I had just two days before leaving again to see what I could figure out.

Well, this is what I figured out.

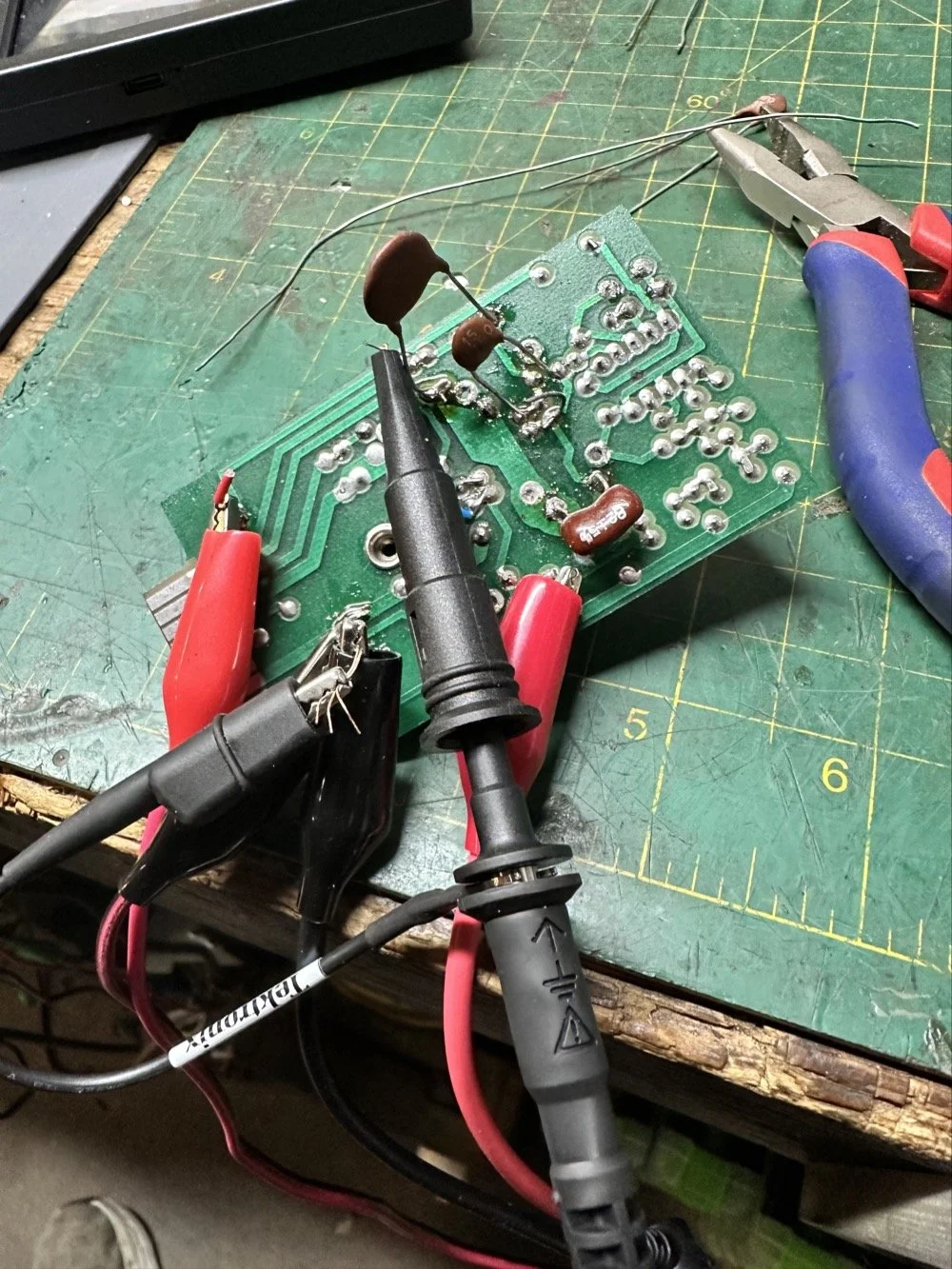

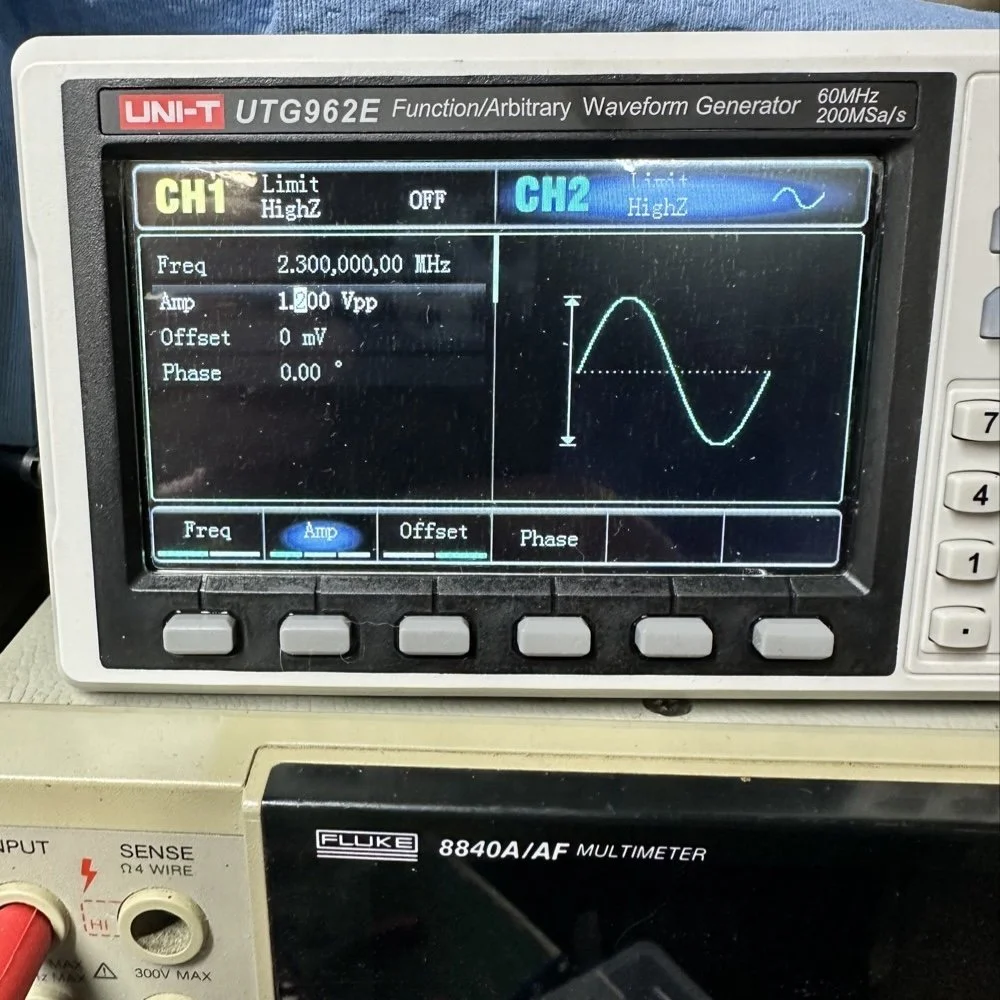

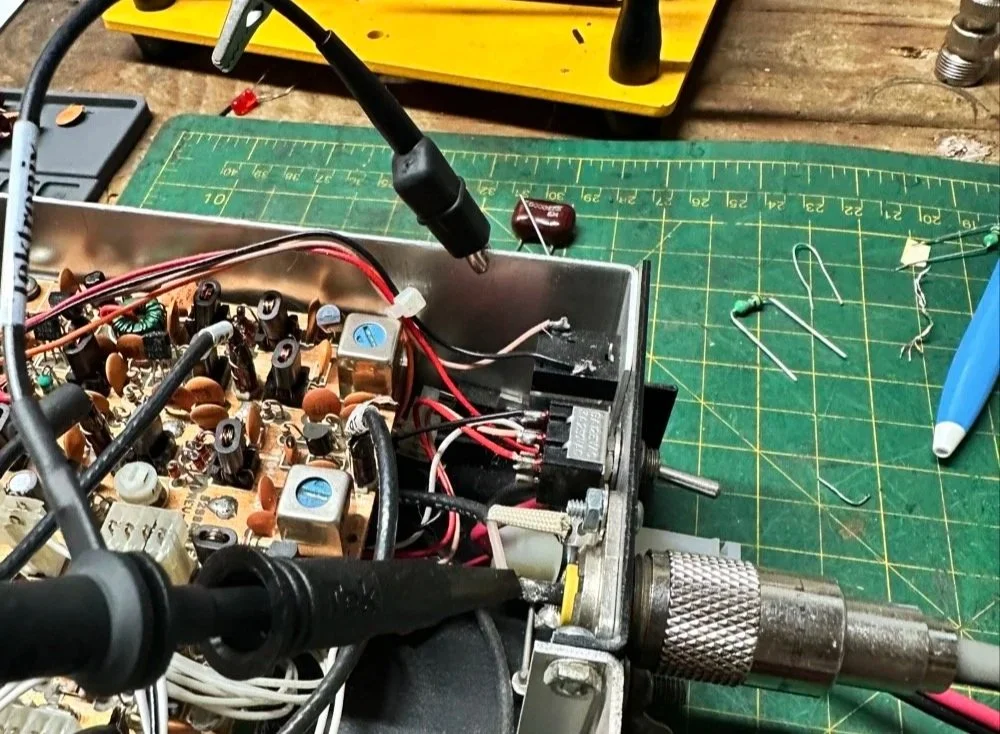

What you see above is a frustration point to be honest. I studied the print long enough to realize I could bring the circuit to life if I had a signal generator and a power supply. To get this to work I soldered several small scrap clippings from component leads to the board in strategic places to be able to connect leads for various devices and you get what you see above. I immediately went down a rabbit hole on signal generators and ended up with a UNI-T UTG962E and it arrived THE DAY BEFORE WE LEFT ON OUR TRIP. I get it going and power up the circuit with the 10 VDC bus and then inject a 2.2 mhz signal from the brand spanking new signal generator into the line (simulating the PTO) to see what I would get at the output… well… nothing. I checked the crystal and I had a clean 9.218 mhz signal at about 700mV going into the mixer chip but my 2.2 mhz injected signal was 50mV (the signal level based solely on the output shown on the block diagram going into the receiver control board as the data sheet for the chip I found didn’t show a signal level threshold that I could find.). This was obviously too low and I started turning up the signal generator and nothing happened at first. I was at 700mV of signal level coming out of the generator and I was getting nothing at the output of my filter. So I start walking it back to the output of the generator. I didn’t have anything at the output of the mixer chip as it turned out, so I check the inputs to the chip on the chip directly and the PTO input was almost non-existent. Turns out that the output impedance of the signal generator and the input impedance of the low pass filter for the mixer chip on the board must be different as it was dropping the level pretty dramatically. (This is something else I have learned while doing this project, you have to observe the impedance between stages or it wont work. ) So what do I do to solve for this? (Remember again I have almost no formal education in this area of expertise) I simply put the scope on the output of the mixer IC itself and slowly start turning up the 2.3 mhz amplitude till Eureka! The mixer sprang to life and I had a product!

Note: I am using a different value here for the PTO reference signal because I didn’t notice that I had changed it till I got the mixer working. But it is fine as the PTO operates from 2.2 mhz up to about 2.7 mhz anyway. The key was getting the bottom of the mixed product below 11.425 mhz when the PTO is at minimum. This will allow tuning through the 60 meter band. But this is why the number in the photo below is 11.520 mhz and not 11.425 mhz.

Now that I have a signal coming out of the mixer IC, I need to see what it going to the receiver control board. You see on the signal path drawing from the NA5N site that he states it should be 50 mV or so there. Well I had nothing coming out of the band module at all. I start looking at the filter and this is when I figure out the filter is all wrong. Back to the drawing board again. I take the week long break and during this time away I dwell on what I had learned and spend even more time trying to learn how this bizarre filter works. It looks somewhat like a regular band pass filter but there are elements that don’t make sense to me. I spent a considerable amount of time studying this problem and decided to order some inductors and when I get back I could replace my home brew ones and see if I had done something wrong there.

Fast forward a week and I went home and had about 5 hours total to figure the whole thing out or it would wait yet another week… I start by replacing the two home brew inductors with two 2.2uH inductors from the variety kit I ordered. Still didn’t work, so there must be something wrong with the capacitors too. All of the caps at this time were class 2 capacitors so that would turn into a problem as they warmed up, but this thing was not working even when it was cold, so the values were wrong is all I could figure. The most logical thing was to strip them all out and start over. I had now gotten my hands on some NPO caps too, this allowed me to build out the filter completely with the correct rating capacitors thereby giving me the confidence that once it is working, it will hold value.

My first batch that I bought was a literal double handful of random NPO capacitors (and a few other ratings mixed in for fun) thrown into a box from eBay. I knew what I was getting so I also picked up some divider boxes to sort them when I got time. Now they are all sorted and I know where to find what when I need it. Of course, I don’t have every conceivable size to choose from but I do have a large assortment and can get by with most projects with what I have. Things like this are what I wished I had learned in trade school… I guess I should have chosen college instead…you know what they say about hindsight though...

The photo of the board above that shows all the leads connecting to temporary test points I soldered to the board has these capacitors on it. They are temporarily soldered on as I am experimenting with various values in different locations to see what will get me to where I need to go.

I tried to use the online calculators but this filter doesn’t fit into any of those models and all the outputs from those tools were not working for me. It looks like the coupling capacitors are also used to also limit the signal level from stage to stage as well. Correct me if I am wrong in this assumption, but tiny little 5 and 8 pF capacitors are not letting a lot of energy through them, even at HF frequencies and there are two in this filter circuit. I can only assume that they are also using these to match impedance as well or a larger value would couple the stages with more signal. Anyway, I was stumped and asking the internet for help is literally begging to be slandered and chastised for being stupid, so I didn’t even bother with that option. That only left experimentation and experimentation is what I did. I put all sorts of outlandish caps in this filter and found success doing it this way. It took me a few hours, not gonna lie, knowing how to calculate these sorts of things would have been immeasurably easier, but I was able to get the signal on the output trace of the band module and it had decent signal level too! Honestly, I am going to revisit the output signal level when I get back home (I may have already done it by the time this goes live on my site) and see if I can attenuate the level somewhat as it is higher than what the base of Q16 on the receiver control board shows in NA5N’s pictogram.

What you are seeing above is the output of one of my Argo 556 radios that I used as a test bed to check the signal levels and such to see what was going on with it. As you can see I simply connected to the output of the radio and looked at the signal going into a 50 ohm dummy load. I did the math (I know, I know… this has not been a great idea for me in this blog post… lol) and it comes out to about 1.8 watts and not 5 watts for this radio (I have not attempted to turn up the transmit power on this unit yet either so it might simply be turned down or something like that. Let me know if my math is wrong here, but 27 volts peak to peak and 50 ohms should give me a power level of 1.82 watts at the antenna connector?

Power= peak voltage (13.5volts) divided by the square root of 2 and then that is divided by resistance.

All that aside, I took the newly minted 60 meter band module up to the shack and setup a Scout 555 and connected it to my home antenna. Tuned the antenna up and started looking for a QSO. I promptly found one and had a short ragchew with VE3USP in Ontario despite some QSB along the way. It works perfectly too. I do have to dial up 600 hz to be on frequency as it is a Scout 555 after all, but that is not a problem!

So I am not completely finished with this module as of yet. I still want to look at that output filter from the mixer and tune it some more. It is close, but it is not right as the signal level is too high. I found I missed a couple of capacitors when I dismantled it to clean it that need to be NPO capacitors instead of what I currently have in place as well. I would also like to improve upon my terrible painting skills if I could figure out a way to do it…lol Seems acrylic craft paint might not be the best solution here…

Next week we get into what happened when I took it to a POTA park… hint: I brought it back home and got inside a little more to fine tune it…. I discuss this next week and show you what I came up with for the mixer output filter ultimately.

To read the other parts:

- Part 1: Initial Conversion and Filter Design

- Part 2: Crystal Selection and Mixer Circuits

- Part 3: Field Testing and Troubleshooting

- Part 4: IF Filter Redesign (this post)

73

WK4DS - David

Converting Ten-Tec Scout 555 to 60 Meters: Complete Band Module Modification Guide [Part 1]

You see it was starting to look pretty daunting since I didn’t understand what the reason for the odd frequency crystal was and that there were 4 tuned filters in each band module. Also the crystal value just didn’t make sense on the surface.

When I first decided I wanted to make a band module for the Ten Tec Scout 555 that was able to get on 60 meters, I had no idea what really was involved.

A little backstory here is kinda needed, you see the Ten Tec Scout 555 has become one of my favorite radios for POTA operations and I even find myself setting one up in the shack to tinker with from time to time. I own 3 Scouts and 2 Argos at the time of this writing if that tells you anything. I don’t know if it is the simple elegance of the radio or the fact that it can operate on almost all of the HF bands in such a small form factor, but I love it. Well there are a few things for sure that draw me to this radio like the fact that these radios have the now infamous Ten Tec full QSK (full break in) keying. This keying works flawlessly too by the way. Another reason for such love for these radios is the amazing receive they have even for such a compromise design. With headphones (or even those little earbuds), it is pretty easy to hear stations in the edge of the noise floor and make contact with them.

Well, if you noticed I said… almost… all the HF bands… This is because we have been granted, by the IARU, some space in the 60 meter band as secondary users.

Some of this band space is open to use with power levels up to 100 watts too. (There has been a recent change that modifies the allocation to allow a bandwidth section that is non-channelized but limits the power to 9.5 watts ERP so play in this area carefully. Basically this new region is a QRP only region for now.) Aside from that though, the Ten Tec Scout 555 can operate quite legally in the other 4 sections… or it could if… there was a 60 meter band module… You see this 60 meter band allocation happened after the Scout 555 production run had ended, so Ten Tec never made a factory band module for the 60 meter band that I am aware of.

I started this journey by digging through the owners manual for the Scout as Ten Tec always shipped complete schematic diagrams with their radios. Sometimes there would be missing insignificant data, but you could trouble shoot the radio just fine with them. Once the radio diagrams were located, I started looking at how the band modules made it change bands.This turned out to really be quite simple but I was missing one or two critical values. You see the Ten Tec Scout 555 band modules have a crystal in them and the frequency on the crystal didn’t make sense…at first.

Above is the schematic and a photo of the board that goes with it showing the crystal that I couldn’t understand. This is what tells the radio what band it is on. Looks pretty straight forward at a glance, doesn’t it? Well look at that XTAL value at the end of the chart for 80 meters. Yeah, it takes a 7.444 mhz XTAL to get to the 80 meter band. So I figure the PTO is something like 3.0 mhz so it can get the first negative harmonic when mixed or something like that…nope…turns out I was totally wrong…

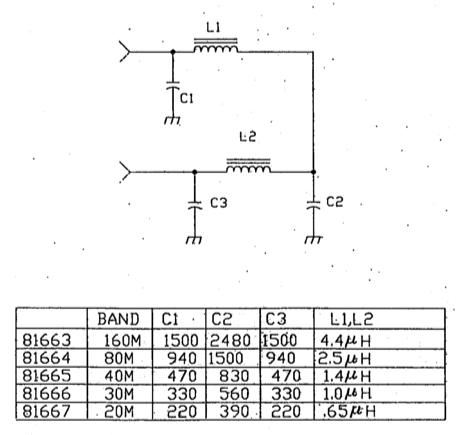

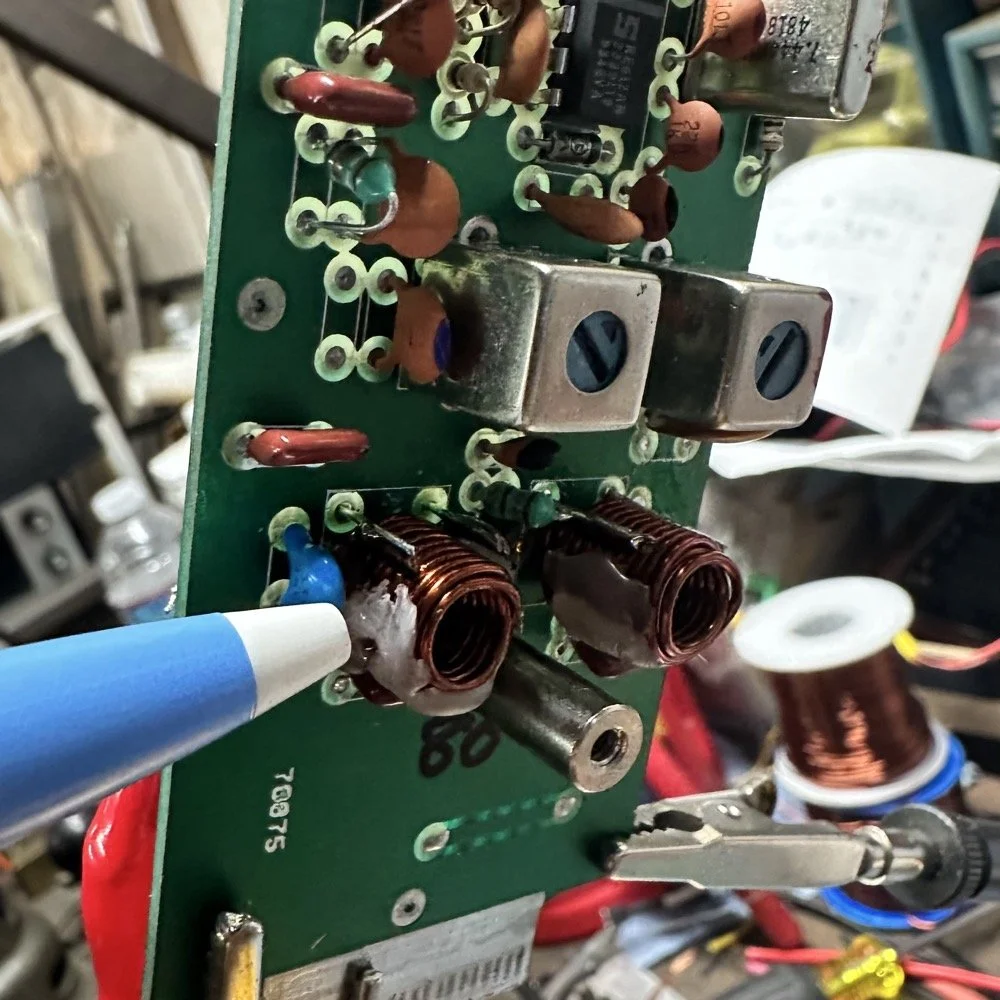

This is the other half of the band module. A classic low pass LC filter and that’s all. This is the output filter that the 50 power amp sends the RF to before it goes to the antenna. Below is what this part of the module looks like. These inductors and capacitors are shielded as they are delivering and filtering considerable power and could interfere with the small voltage levels on the other board that sits right beside it if they were not in the “can” or otherwise known as a ground shield. I don’t know why there is a hole in the shielding either as there is no adjustable parts inside the “can”. I chose this particular 80 meter band module for another reason as well. I have been inside this filter circuit before. When I acquired this module, the fellow I got it from told me it was dead and gave it to me. Turned out to be a broken lead on one of the inductors in this can. It took me a while to desolder this monstrosity to be able to access the parts inside of it. But persistence paid off as I was able to get it repaired and back in operation. I took a lead cut from a transistor and soldered it to the wire on the inductor and simply re-soldered it to the board and it came right back to life. So if you have a module that just stops transmitting all together, I recommend you pull the lid here and look at the inductors to see if one is broken free from the board, that might be all that is wrong with it. I also hot glued the toroids in place to help prevent this from happening again. Anyway, back to the project at hand…

I also looked inside several band modules to see what the differences were and I found some interesting things when I did. For starters, the 10 and 12 meter band modules both use the same circuit boards. They just leave out the second crystal and the switch parts for the second crystal and put a crystal in it for the 12 meter band only when configured for 12 meters. I guess, to be fair, I should have also figured out how the PTO worked as well then I could have figured out the reason for the odd crystal values, but here we are…

Another thing I found was that the engineers at Ten Tec used whatever circuit board blanks that they had on hand to build the band modules apparently. I say this because I found 10m circuit boards (the ones meant for two crystals and the switch) fleshed out with parts to make them into 40 m band modules. (Like the one in the photo above) They apparently just used whichever ones they had on hand at the time. Needless to say, what I thought was going to be simple was starting to turn into a pretty major endeavor.

You see it was starting to look pretty daunting since I didn’t understand what the reason for the odd frequency crystal was and that there were 4 tuned filters in each band module. Also the crystal value just didn’t make sense on the surface. The values were all over the place. I was about to throw in the towel calling it just too complicated, even though the parts count in a band module is really low…till I found two things. One was I looked up what the “555 timer” on the board actually was (Here is a hint, it aint no timer) and the other was NA5N’s website.

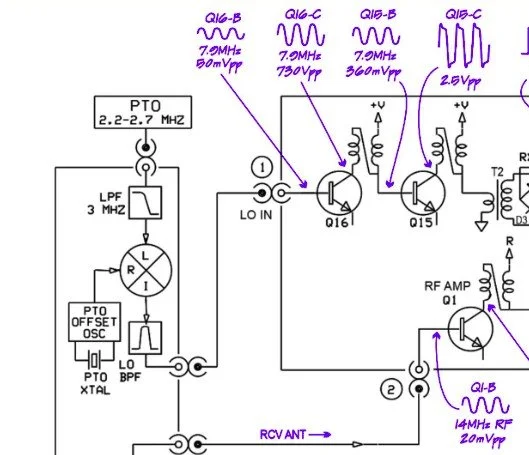

Excerpt from NA5N’s website showing the level of detail these drawings contain.

NA5N’s Scout 555 page is a figurative gold mine of information with just plain cash money piled on top of it, (just to drive this point home take a look at the piece above I grabbed for reference). I can not thank him enough for this information as without it I would not have been able to get this project working as quickly as I did. He also has some really interesting mods he has done to his own radio as well. If you want to perform his mods on your Scout, he gives you detailed information on what is done and literally how to do it…step by step almost. The greatest part of his page though is his info graphics he has built and placed there. These graphics show all sorts of information that the radio schematics leave out.

This and MUCH more is available on the NA5N website.

Things like the frequency path (pictured above) through the radio in a chart so you can understand how the engineers at Ten Tec arrived at each band frequency with these plug in modules and a PTO. Complete with oscilloscope test point and what you should be seeing at these points! Like I said, a gold mine buried in cash money…

Based on his chart I went through the band module and looked at the filters for the various circuits and decided (more like assumed based on the values of the parts) that I could simply re-tune an 80 meter module and “push” it up to 5.3305 mhz easily enough and without too much fuss…nothing could have been further from the truth.

So I start tinkering with the filters and piping them through the nanoVNA into the s21 input so I can see the filter shape and all is well from what I can see. Turns out the low pass 80 meter band module filter cut off frequency was about 5.5 mhz or so to start the rolloff so the 60 meter band was still in the pass band! One down three to go! Next I figured out that the PTO is the same for every module since it is part of the radio and not in any of the modules so that filter also didn’t need any mods. This left two filters to re-tune, just so happens it is the two with the adjustable inductors in them. So I start with the LO BPF (Local Oscillator Band Pass Filter) that filters the signal passing through the radio from the antenna. Why they call it the same thing as the LO BPF that is in the output of the mixer chip is beyond me, but here we are… This didn’t go well as I was not able to get enough adjustment out of the inductor slugs to get the passband up to 5.350 mhz, shoot I couldn’t get it to tune up past 4.5mhz if memory serves me. It was far enough that I couldn’t get it work so I looked at what I had and decided to wind some air-core inductors to a lower value and see what I could do like that.

Well, to be honest, I don’t know how I was so successful here. Maybe it was the sheer audacity in the fact that I was woefully unskilled in building filters for HF or the mind boggling lack of knowledge of how filters work and how to make them, but I got it almost perfect on the first try! I made a couple different inductors by winding magnet wire on a 1/4-28 bolt (that’s a little over a 6mm bolt for the rest of the world) and the threads made getting good tight coil layers easy. I borrowed my friend’s LCR meter and measured them and blissfully declared them good to go at 2.0uH each. Did I mention this is a budget LCR meter and I have no way of knowing what the level of calibration is for this part of the meter? I also learned later that I can measure my inductors with a signal generator and a oscilloscope. Guess who now owns a signal generator as well as an oscilloscope...

Once wound and “measured” in the board they went! I then tinkered with the capacitors till the pass-band looked close to what I thought it should look like. (I had also learned from the wonderful world of youtube that I should see less than 1dB of loss in the pass-band and the 3dB cutoff point is where the filter technically is measured..typically.) As I mention in a bit, I used the wrong kind of capacitors (the little blue ones) to start with, although the module did work like this, I updated it with NPO capacitors ultimately as well.

I went down a long path of learning on this project, if you haven’t already noticed from the inserted comments in the story. I have very little formal training in Electrical Engineering, you see I went to a two year trade school back in the 1980s and basically got the “intro to electronics” that EE’s would get before learning things like matching the impedance of the filter to the next stage and to use temperature stabilized capacitors in RF filters so they don’t move the pass-band around when they get warm. NPO capacitors have become my best friends here…lol. A hint for my peeps who also didn’t study RF in college, look at the circuit board above that has the crystal on it. You will see the little capacitors on that board and some have little painted tops on them. This indicates NPO capacitors when the letter designation will not fit. I have now purchased a lifetime supply of these caps off of eBay…haha.

Anyway, now the pre-amp band-pass filter was functioning like it should. One to go…

Tune in for part two where we get into the problems I had to solve to get this module working and how well it works now that I have figured out my mistakes.

Continue reading the series:

- Part 1: Initial Conversion and Filter Design

- Part 2: Crystal Selection and Mixer Circuits

- Part 3: Field Testing and Troubleshooting

- Part 4: IF Filter Redesign (this post)

73

WK4DS - David

![Building a 60m Band Module for Ten-Tec Scout 555: Crystal Selection & Filter Design [Part 2]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d17806ce65eba00011667cb/1768486316134-5KK47YMDB3P45BK25B4N/IMG_1141.jpg)